A Philosophy of Software Design

A Philosophy of Software Design is a short yet to-the-point book on high level ideas on how to design a software system with less complexity. It's a book I would recommend to every entry-level software engineer.

This note mostly consists of quote-worthy excerpts from the book and aims to serve as a verbose version of the book's table of contents. Readers can use this note to quickly browse the main arguments of the book, or to locate the chapters of interest that deserves reading.

A tip for those who decide to read the book: pay attention to examples, red flags and "taking it too far" sections of the book, which are of great value but are not covered by this note for brevity.

Ch1: Introduction (It's All About Complexity)

The greatest limitation in writing software is our ability to understand the systems we are creating.

Two general approaches to fighting complexity:

- Eliminate complexity by making code simpler and more obvious.

- Encapsulate complexity so that programmers can work on a system without being exposed to all of its complexity at once.

Ch2: The Nature of Complexity

The ability to recognize complexity is a crucial design skill.

Definition: complexity is anything related to the structure of a software system that makes it hard to understand and modify the system. It is more apparent to readers than writers.

Symptoms: complexity manifests itself in three general ways:

- Change amplification: a seemingly simple change requires code modifications in many different places.

- Cognitive load: how much a developer needs to know in order to complete a task. E.g. APIs with many methods, global variables, inconsistencies, dependencies between modules. - Sometimes an approach that requires more lines of code is actually simpler, because it reduces cognitive load.

- Unknown unknowns: it's not obvious which pieces of code must be modified to complete a task, or what information a developer must have to carry out the task successfully.

Causes: complexity is caused by two things -- dependencies and obscurity.

- A dependency exists when a given piece of code cannot be understood and modified in isolation; the code relates in some way to other code, and the other code must be considered and/or modified if the given code is changed.

- Obscurity occurs when important information is not obvious. - Obscurity is often associated with dependencies, where it is not obvious that a dependency exists. - Inconsistency is also a major contributor. - Obscurity comes about because of inadequate documentation. However, it's also a design issue. The need for extensive documentation is often a red flag that the design isn't quite right.

Complexity isn't caused by a single catastrophic error; it accumulates incrementally.

Ch3: Working Code Isn't Enough (Strategic vs. Tactical Programming)

- Tactical programming: short-sighted. The main focus is to get something working, such as a new feature or a bug fix. This is how systems becomes complicated.

- Strategic programming: to realize that working code isn't enough. Most of the code in any system is written by extending the existing code base, so your most important job as a developer is to facilitate those future extensions. - Proactive investments: find a simple design for each new class; try a couple of alternative designs and pick the cleanest one; try to imagine a few ways in which the system might need to be changed in the future and make sure that will be easy with your design; writing good documentation. - Reactive investments: when you discover a design problem, don't just ignore it or patch around it; take a little extra time to fix it.

Ch4: Modules Should Be Deep

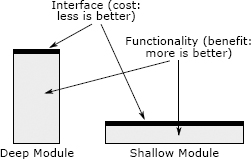

Think of each module in two parts: an interface and an implementation. The best modules are those whose interfaces ware much simpler than their implementations.

The interface contains two kinds of information:

- Formal information: e.g. signature.

- Informal information: e.g. high-level behavior, constraints on the usage of a class, etc. If a developer needs to know a particular piece of information in order to use a module, then that information is part of the module's interface.

An abstraction is a simplified view of an entity, which omits unimportant details. An abstraction that omits important details is a false abstraction.

Red flag: shallow modules don't help much in the battle against complexity, because the benefit they provide is negated by the cost of learning and using their interfaces.

Unfortunately, the value of deep classes is not widely appreciated today. Students are often taught that the most important thing in class design is to break up larger classes into smaller ones. The same advice is often given about methods: "Any methods longer than N lines should be divided into multiple methods" (N can be as low as 10). This approach results in a large number of shallow classes and methods, which add to overall system complexity.

Interfaces should be designed to make the common case as simple as possible.

Ch5: Information Hiding (and Leakage)

Information hiding: each module should encapsulate a few pieces of knowledge, which represent design decisions. The knowledge is embedded in the module's implementation but does not appear in its interface,so it is not visible to other modules.

Information leakage occurs when a design decision is reflected in multiple modules. This creates a dependency between the modules. Also, if a piece of information is reflected in the interface for a module, then by definition it has been leaked.

One common cause of information leakage -- Temporal decomposition: the structure of a system corresponds to the time order in which operations will occur. Consider an application that reads a file in a particular format, modifies the contents of the file, and then writes the file out again. Both the file reading and file writing steps have knowledge about the file format, which results in information leakage.

Focus on the knowledge that's needed to perform each task, not the order in which tasks occur.

Information hiding can often be improved by making a class slightly larger.

Overexposure (red flag): if the API for a commonly used feature forces users to learn about other features that are rarely used, this increases the cognitive load on users who don't need the rarely used features.

Ch6: General-Purpose Modules are Deeper

The sweet spot: make classes somewhat general-purpose -- the module's functionality should reflect your current needs, but its interface should not. Instead, the interface should be general enough to support multiple uses.

Ch7: Different Layer, Different Abstraction

Red flag: if a system consists of adjacent layers with similar abstractions, this suggests a problem with the class decomposition.

Pass-through methods: methods that do little except invoke other methods, whose signatures are similar or identical. They are shallower as they increase the interface complexity of the class, but they don't increase the total functionality of the system. They indicate that there is confusion over the division of responsibility between classes.

Interface of a class should normally be different from its implementation: the representations used internally should be different from the abstractions that appear in the interface.

Pass-through variables: variables that are passed down through a long chain of methods. They add complexity because they force all of the intermediate methods to be aware of their existence, even though the methods have no use for the variables. Furthermore, if a new variable comes into existence, you may have to modify a large number of interfaces and methods to pass the variable through all of the relevant paths.

Ch8: Pull Complexity Downwards

It's more important for a module to have a simple interface than a simple implementation.

Ch9: Better Together Or Better Apart

One of the most fundamental questions in software design: given two pieces of functionality, should they be implemented together in the same place, or should their implementations be separated?

Subdividing creates additional complexity:

- Some complexity comes just from the number of components: the more components, the harder to keep track of them all.

- Additional code to manage the components.

- Separation makes it harder to see the components at the same time, or even be aware of their existence.

- Code duplication.

A few indications that two pieces of code are related:

- They share information.

- They are used together (only compelling if bidirectional).

- They overlap conceptually.

- It's hard to understand one of the pieces of code without looking at the other.

We should:

- Bring together if information is shared.

- Bring together if it will simplify the interface.

- Bring together to eliminate duplication.

- Separate general-purpose and special-purpose code. Failing to do so is usually a red flag.

Ch10: Define Errors Out Of Existence

Exception handling is one of the worse sources of complexity in software systems.

- Exception handling code is inherently more difficult to write than normal-case code. Furthermore, it creates opportunities for more exceptions.

- It's difficult to ensure that exception handling code really works. Some exceptions can't easily be generated in a test environment.

Code that hasn't been executed doesn't work.

The exceptions thrown by a class are part of its interface; classes with lots of exceptions have complex interfaces, and they are shallower than classes with fewer exceptions.

Techniques for combating complexity from exceptions:

- The best way to eliminate exception handling complexity is to define your APIs so that there are no exceptions to handle.

- Exception masking: reduce the number of places where exceptions must be handled.

- Exception aggregation: handle many exceptions with a single piece of code. - Exception aggregation works best if an exception propagates several levels up the stack before it is handled. This allows more exceptions from more methods to be handled in the same place. This is the opposite of exception masking: masking usually works best if an exception is handled in a low-level method. For masking, the low-level method is typically a library method used by many other methods, so allowing the exception to propagate would increase the number of places where it is handled. Masking and aggregation are similar in that both approaches position an exception handler where it can catch the most exceptions, eliminating many handlers that would otherwise need to be created.

- Just crash when it makes sense to do so.

By the same token, it also makes sense to define other special cases out of existence.

C11: Design it Twice

Designing software is hard, so it's unlikely that your first thoughts about how to structure a module or system will produce the best design. You'll end up with a much better result if you consider multiple options for each major design decision.

Ch12: Why Write Comments? The Four Excuses

When developers don't write comments, they usually justify their behavior with one or more of the following excuses:

- Good code is self-documenting.

- I don't have time to write comments.

- Comments get out of date and become misleading.

- The comments I have seen are all worthless. Why bother?

All are debunked in the book.

Good documentation helps with two of three ways in which complexity manifests itself in software systems: cognitive load and unknown unknowns.

Ch13: Comments Should Describe Things that Aren't Obvious from the Code

- Decide on conventions for commenting.

- Don't repeat the code. - Comments at the same level of details as the code is not useful and a red flag. - Ask yourself a question: could someone who has never seen the code write the comment just by looking at the code next to the comment. If the answer is yes, the comment is not useful.

- Comments augment the code by providing information at a different level of detail: - Low-level comments add precision. - High-level comments offer intuition.

- If interface comments must also describe the implementation, then the class/method is shallow (red flag).

Ch14: Choosing Names

Good names are a form of documentation/abstraction.

Good names have two properties: precision and consistency.

- Precision

- Vague names are a red flag.

- It's fine to use generic names like

iandjin a loop. But if the loop gets so long that you can't see it all at once, then a more descriptive name is in order. - Also avoid names that are too specific. - If you find it difficult to come up with a name for a particular variable that is precise, intuitive, and not too long, it suggests that the variable may not have a clear definition or purpose. - Consistency - Always use the common name for the given purpose. - Never use the common name for anything other than the given purpose. - Make sure that the purpose is narrow enough that all variables with the name have the same behavior.

The greater the distance between a name's declaration and its uses, the longer the name should be.

Ch15: Write The Comments First

- Delayed comments are bad comments.

- Write the comments first.

- Comments are a design tool. - Comments serve as a canary in the coal mine of complexity. If a method or variable requires a long comment, it is a red flag that you don't have a good abstraction.

- Early comments are fun comments.

- Early comments are not really too expensive.

Ch16: Modifying Existing Code

- Practice strategic programming.

- Keep the comments near the code, which is the best way to ensure that comments get updated.

- Avoid duplicated comments.

- Comments belong in the code, not the commit log.

- Higher-level comments are easier to maintain.

Ch17: Consistency

Consistency creates cognitive leverage: once you have learned how something is done in one place, you can use that knowledge to immediately understand other places that use the same approach. Examples include names, coding style, interfaces, design pattern, and invariants.

Ensuring consistency:

- Document the most important overall conventions.

- Enforce conventions with automated tools to check for violations.

- When in Rome, do as the Romans do.

- Don't change existing conventions. - Having a "better idea" is not a sufficient excuse to introduce inconsistencies. The value of consistency over inconsistency is almost always greater than the value of one approach over another.

Ch18: Code Should Be Obvious

"Obvious" is in the mind of the reader: it's easier to notice that someone else's code is non-obvious than to see problems with your own code. Thus, the best way to determine the obviousness of code is through code reviews.

Things that make code more obvious:

- Choosing good names.

- Consistency.

- General-purpose techniques: - Judicious use of white space. - Comments.

Things that make code less obvious:

- Event-driven programming.

- Generic containers.

- Different types for declaration and allocation.

- Code that violates reader expectations.

Software should be designed for ease of reading, not ease of writing.

Ch19: Software Trends

This chapter is a rather opinionated comment on recent trends in software development.

- OOP & Inheritance - Interface inheritance: in order for an interface to have many implementations, it must capture the essential features of all the underlying implementations while steering clear of the details that differ between the implementations. This notion is at the heart of abstractions. - Implementation inheritance: should be used with caution as it creates dependencies between the parent class and each of its subclasses. Try to separate the state managed by the parent class from that managed by subclasses.

- Unit tests: they play an important role in software design because they facilitate refactoring.

- TDD: it focuses attention on getting specific features working, rather than finding the best design. This is tactical programming pure and simple. The units of development should be abstractions, not features.

- Getters and setters: they are shallow methods, so they add clutter to the class's interface without providing much functionality.

Ch20: Designing for Performance

How should performance considerations affect the design process?

- Develop an awareness of which operations are fundamentally expensive. - Network communication. - I/O to secondary storage. - Dynamic memory allocation. - Cache misses. - ...

- Measure before modifying.

- Design around the critical path.